Press Release – To70 joins A4Climate project

A4CLIMATE – Cutting the Clouds: Europe’s Push to Reduce Aviation’s Climate Impact. A European Initiative for Smart, Climate-Compatible and Competitive Aviation

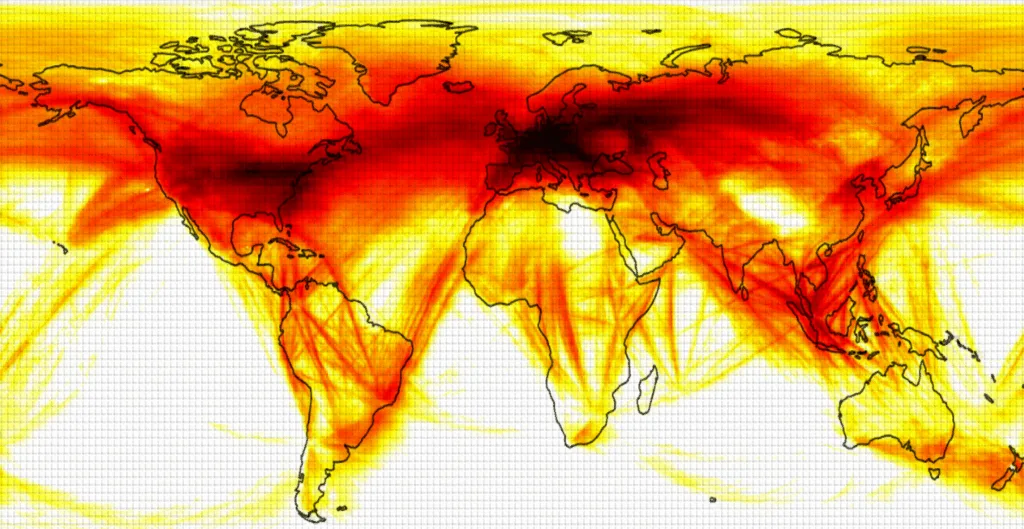

Aviation contributes to global warming through both CO₂ emissions and non-CO2 effects such as contrails. These line-shaped ice clouds form at altitudes of 8 to 14 kilometres under very cold and humid atmospheric conditions. Although contrails persist for only a few hours, their annual warming effect is comparable to that of all aviation-related CO₂ accumulated in the atmosphere since the beginning of aviation. Therefore, the EU has mandated the monitoring of these non-CO₂ effects by 2028.

The European research project A4CLIMATE aims to help significantly reduce aviation’s climate impact by minimizing contrail formation through smarter flight routing, advanced engine technologies and sustainable alternative fuels. Led by the German Aerospace Center (DLR), the project brings together 17 partners from nine countries, including experts from universities, industry leaders and stake holders. A4CLIMATE strengthens the scientific understanding of engine emissions, contrails and their climate effects, and translates this knowledge into practical solutions for more climate-compatible flight operations.

“A4CLIMATE explores contrails and their climate impact. Our findings will advance knowledge on how much specific engine technologies and smart flight operations can actually reduce the warming caused by contrails,” says project lead Christiane Voigt from DLR.

Using state-of-the-art models and measurement systems, the project employs a cutting-edge contrail prediction tool to assess 400 regular commercial flights designed to avoid contrail formation. Satellite data, ground observations and in-flight measurements are combined with advanced modelling to analyze how modern propulsion systems and alternative fuels can reduce contrails. A4CLIMATE also provides comprehensive atmospheric datasets on contrails, cirrus clouds and humidity for the validation of weather and contrail models.

Flights to Reduce Contrails

The first series of demonstration flights operated by TUIfly – supported by FLIGHTKEYS and DLR – has now begun. The core idea is simple: to avoid atmospheric regions where warming contrails are likely to form. Cost-based avoidance algorithms by FLIGHTKEYS calculate the climate optimal flight route and weigh the operational cost of trajectory adjustments against the climate benefit from reduced contrail formation. Since the beginning of the year, TUIfly has been regularly testing contrail avoidance in practice and has analyzed hundreds of their regular flights. The aim of these trials is to steer aircraft around air layers in which climate-warming contrails could develop.

Early demonstrations revealed two key challenges. First, manual data handling slowed feedback to pilots and operational teams. Second, real-world conditions, such as congested air space, flight delays, rapid weather changes and turbulence, often made contrail-optimized routes difficult to implement. In some cases, longer flight paths required to avoid contrails increased CO₂ emissions, potentially reducing the intended climate benefit. This highlights the need to carefully balance the trade-off between CO₂ and non-CO₂ effects.

A4CLIMATE is now addressing these challenges through a fully automated data pipeline that processes flight plans, provides instantaneous feedback to pilots and airlines, and collects real-time performance data. Satellite observations are used to verify whether contrail avoidance strategies are effective in practice. Additionally, comprehensive modeling will evaluate trade-offs in climate impact including uncertainties. These insights will guide the development of reliable and scalable tools to support less impactful aviation operations across Europe.

Innovative engines and alternative fuels

In parallel, the project investigates how modern engine designs and alternative fuels influence contrail formation. Laboratory tests on the ground and at airports are complemented by dedicated flight campaigns. For the new test flights in November 2025, DLR’s research aircraft Falcon 20E follows selected TUIfly observations flights specifically routed through contrail-forming regions. The Falcon 20E measures the resulting contrail properties from the TUIfly aircraft equipped with innovative, low-sooting lean-burn engines.

Soot particles serve as nuclei for ice crystal formation in contrails. While ground tests show that these engines emit extremely low soot levels, the impact of reduced soot on contrail formation and ultimately on climate warming remains unknown. Over the coming years, A4CLIMATE will address this knowledge gap and compare the climate benefits of various mitigation strategies, including modern engines, alternative fuels and operational measures.

Statement by To70

To70 provides advisory services on aviation and airspace operations and environment. We support Governments, Airports, ANSPs and large scale research groups. To70 has previously collaborated with DLR, DWD and AerLabs to support the European Commission DG CLIMA in developing the EU MRV legislation. Within A4Climate To70 aims to provide operational insights and analysis on the research outcomes, and to translate these outcomes to both the sector and to policy makers where possible. This will be done through mapping of operational costs and impacts as well as through policy recommendations. To70 looks forward to contributing to A4Climate by providing a clear translation of findings and outcomes to relevant stakeholders.

“This project allows us to apply our expertise on how aviation really works, thereby ensuring that research outputs can make a real-life impact.” – Vincent de Haes, A4Climate project manager To70

About the project

Launched in February 2025 with a four-year duration, A4CLIMATE is funded by the “Horizon Europe”-Programme by the European Union (Grant Agreement no. 101192301) to provide practical solutions that support sustainable aviation. The project gathers 17 partners from nine countries, forming a consortium led by German Aerospace Center (DLR), and comprising academic institutions, industry leaders, and consulting experts. Together, they collaboratively investigate strategies to minimize the climate impact of contrails and advance competitive aviation practices:

- German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR, Germany), Coordinator

- Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD, Germany)

- Institutul National De Cercetare-Dezvoltare Aerospatiala “Elie Carafoli”- Incas Bucuresti (INCAS, Romania)

- Max Planck Institute for Chemistry (MPIC, Germany)

- Imperial College of Science Technology and Medicine (IMPERIAL, United Kingdom)

- Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz (JGU, Germany)

- Goethe University Frankfurt (GU, Germany)

- University Of Leeds (ULEEDS, United Kingdom)

- The University of Reading (UREAD, United Kingdom)

- FLIGHTKEYS GmbH (FKY, Austria)

- To70 (To70, The Netherlands)

- PNO Innovation Germany (PNO, Germany)

- Sopra Steria Group (SSG, France)

- TUIfly GmbH (TUI fly, Germany)

- Breakthrough Energy (BE, United States)

- Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich (ETH, Switzerland)

- Eurocontrol – European Organisation for The Safety Of Air Navigation (EUROCONTROL, Belgium)

For more information, visit

- A4Climate Website: www.a4climate.eu

- Follow us on Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/company/a4climate/

Disclaimer

The information contained in this press release reflects the views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union nor CINEA. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

The additional revenue stream for local farmers could be generated by selling agricultural residues which would otherwise be considered waste, such as rice straw and sugarcane bagasse. This could significantly enhance the livelihoods of local farmers and remarkably contribute to the rural economy. Moreover, new opportunities and markets may arise for the farmers by cultivating energy crops specifically for SAF production.

The additional revenue stream for local farmers could be generated by selling agricultural residues which would otherwise be considered waste, such as rice straw and sugarcane bagasse. This could significantly enhance the livelihoods of local farmers and remarkably contribute to the rural economy. Moreover, new opportunities and markets may arise for the farmers by cultivating energy crops specifically for SAF production.

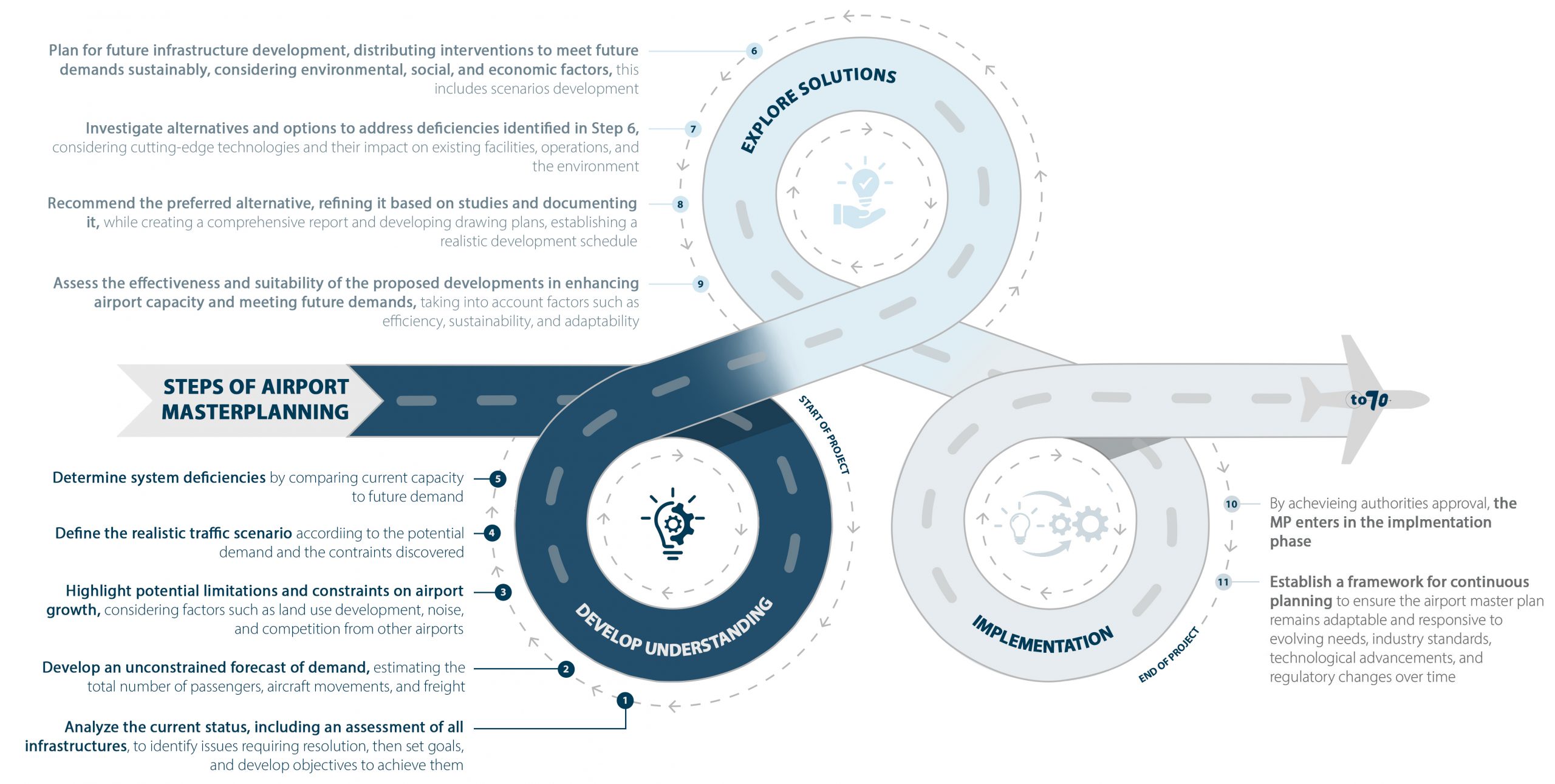

Meticulously planned infrastructure, including runways, taxiways, and aprons, not only streamlines aircraft movements but also minimizes taxi times, elevating overall operational efficiency. Crucial to meeting both current and future demands, resource optimization and capacity planning are prioritized, featuring flexible layouts adaptable to diverse aircraft sizes. Resilience is inherent, with contingency plans and backup systems in place, ensuring uninterrupted operations even in the face of unexpected disruptions. Similarly, the landside infrastructure adheres to this concept to amplify the passenger experience as previously outlined.

Meticulously planned infrastructure, including runways, taxiways, and aprons, not only streamlines aircraft movements but also minimizes taxi times, elevating overall operational efficiency. Crucial to meeting both current and future demands, resource optimization and capacity planning are prioritized, featuring flexible layouts adaptable to diverse aircraft sizes. Resilience is inherent, with contingency plans and backup systems in place, ensuring uninterrupted operations even in the face of unexpected disruptions. Similarly, the landside infrastructure adheres to this concept to amplify the passenger experience as previously outlined.